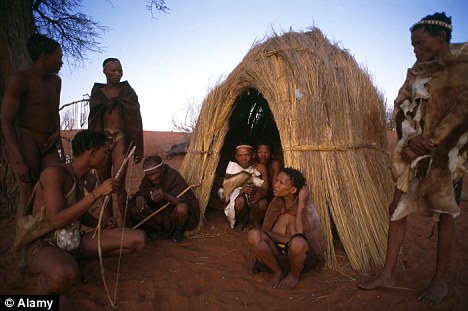

Learning a thing or two from the past…Part 1, 21st century americans are not the first to minimalize.

This is a lengthy ramble. So long in fact, that I have broken it into several posts to be trickled out over the coming days, weeks, or months. Skip on to the fun stuff if you aren’t interested in Minimalist* philosophy. There’s a lot of recent talk about Minimalism as a social movement. Not long ago, it was associated with artists and aesthetes, wanderers, mystics, and philosophers. That is to say, the fringe element, outsiders, and weirdos. These things come in cycles and I think, as a backlash against generations of sell-out philosophy and the creation of a professional consumer class, many people are reaching for something new.

We come to learn that everything old is new again.

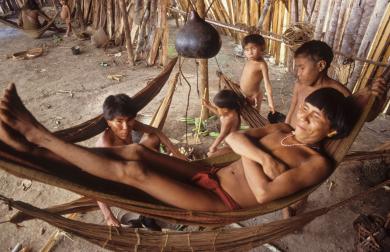

I’ve been looking into history and prehistory on a full-time basis for many decades now. As hard to believe as it may be, I even get paid a salary to do it. One of my professional interests involves tools, tool-kits, and strategies for surviving that various people have come up with for dealing with the world. As a primitive skills-survival instructor and full-time frugalist I think it important to not reinvent a lifeway when we have millennia of ancestors who dealt with most of the same issues we do today.

For most humans, for most of our history, owning too much stuff has never really been an issue. We had what we needed and either made what we needed or did without the things we didn’t have. It brings a smile to my face to know that more than 2,400 years ago, well-to-do people in China, India, and the Middle East were contemplating the nature and evils of acquiring Stuff; even writing about it. That’s not to say that I have immediate plans to become a wandering mendicant like a medieval friar (as appealing as that might sound to some) but I do have an interest in lightening my material load and some very specific goals for the coming year.

My foundation as a minimalist – I have been thinking about what stuff a person needs to survive since I was a teenager. Like virtually every young boy, I had grand ideas of escaping the family and traveling unhindered across the world. I devoured Jack London and Mark Twain stories as a kid. I loved the extensive and well-thought out gear lists provided in the Boy Scout Handbook, the Explorer’s Handbook, and the Philmont Guides. I read Larry Dean Olsen’s great book of Outdoor Survival Skills and Colin Fletcher’s The Complete Walker. I read about the mountain men of the fur trade, and always, took note of what they carried or didn’t seem to need. I would copy lists into a notebook and ponder them while sitting in some boring high school class, making my own lists of what I have, what I need, and what I want. This thinking encouraged me to work and save money to buy a better knife, backpack, or stove. I was probably the only kid I knew who wanted, and got, a file and whetstone for Christmas one year (my grandpa was good that way). My friends and I spent our teens and early twenties hiking and camping year round, mostly in the woods of the Ozarks in southern Missouri testing our mettle at that time in life time when all teenagers know they are invincible. Some of us even made it to Europe, Asia, Africa, and beyond.

In a modern sense of survivalist, many people look to the military or the loonies of teh mainstream media. Often, military service is the time when young men and women are introduced to such things for the first and only time. Realistically however, the military itself acknowledges it’s shortcomings on a personal basis as (with the exception of a few special operations units) its entire system is dependent on lengthy and complex supply lines, support chains, and de-emphasis of the individual and personal decision making. Military survival is therefore, approached as a means of keeping alive until help arrives. Great for fighting a war, but not always so good when you are turned loose into the world.

In a modern sense of survivalist, many people look to the military or the loonies of teh mainstream media. Often, military service is the time when young men and women are introduced to such things for the first and only time. Realistically however, the military itself acknowledges it’s shortcomings on a personal basis as (with the exception of a few special operations units) its entire system is dependent on lengthy and complex supply lines, support chains, and de-emphasis of the individual and personal decision making. Military survival is therefore, approached as a means of keeping alive until help arrives. Great for fighting a war, but not always so good when you are turned loose into the world.

Coming up next…Ultra Minimalists Part2. Let’s look at a military example anyway: Romans.

* here are a few links to modern Minimalists of various ilks and philosophical merit. A journey through these links will hint at the breadth and depth of people on different paths but moving in the same direction.

- http://www.theminimalists.com/ (a good read)

- http://www.becomingminimalist.com/

- http://zenhabits.net/

- http://mnmlist.com/

- http://www.practicalcivilization.com/ (a promising start)

- http://permaculturegrin.wordpress.com/

- http://soulflowerfarm.blogspot.com/

- http://loveandtrash.com/

- http://www.clickclackgorilla.com/

- http://www.thetinylife.com/

- http://www.svdreamkeeper.com/

- http://www.relaxshacks.blogspot.com/

- http://huntergathercook.typepad.com/huntergathering_wild_fres/

- http://www.whittleddown.com/

- http://thewildgarden.ca/

- and finally, The Story of Stuff project

Read, research, think, and enjoy!

Go to Part 2

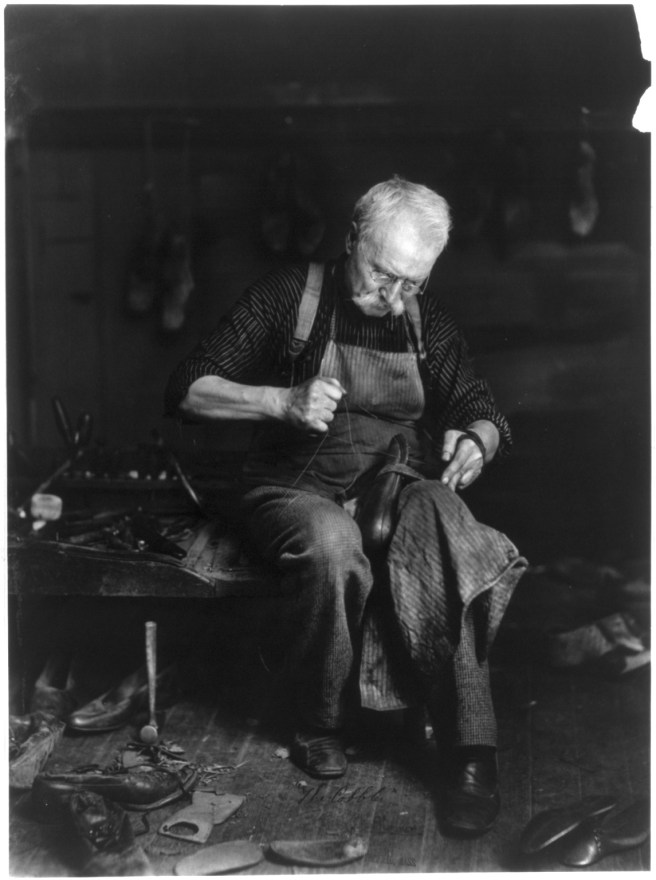

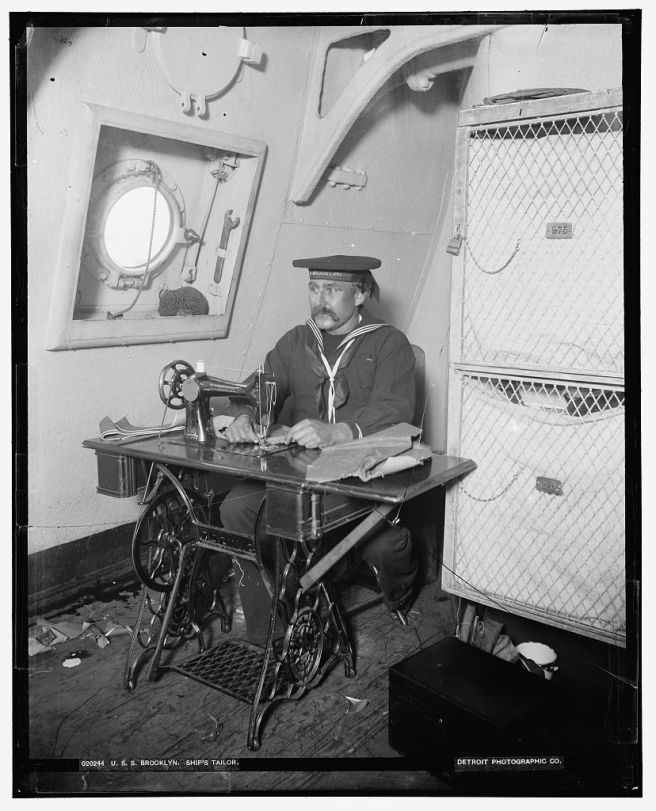

Makers are the hope. We’re out there. Doing things and making stuff. Fending for ourselves in an hostile but lethargic world of expected and nearly enforced consumerism. Once you realize the machine doesn’t work, you can realize it doesn’t really exist.

Makers are the hope. We’re out there. Doing things and making stuff. Fending for ourselves in an hostile but lethargic world of expected and nearly enforced consumerism. Once you realize the machine doesn’t work, you can realize it doesn’t really exist.

Why not go make something? Your great grandparents did.

Why not go make something? Your great grandparents did.