From the Road to Glamperland Facebook page. A very interesting all or mostly wooden home built camper trailer. It has two simple slide-outs, a nice little kitchen set-up and I suspect the benches fold out to be the bed. I really like the water tank on the roof. I have been looking for a vintage looking tank to use for quite a while now but so far, no luck.

From the Road to Glamperland Facebook page. A very interesting all or mostly wooden home built camper trailer. It has two simple slide-outs, a nice little kitchen set-up and I suspect the benches fold out to be the bed. I really like the water tank on the roof. I have been looking for a vintage looking tank to use for quite a while now but so far, no luck.

Tag: DIY

Leather Dopp Kit

A small toiletries bag made from a wax-impregnated leather. The design is essentially that of a very small 18th century portmanteau. Included here are some of the basic tools-of-the-trade for scale and perspective. I think leather work is appealing to me, in part, due to the honest simplicity and lack of power tools. Most projects can be accomplished with a sharp knife, straight-edge, awl and some stitching needles.

A small toiletries bag made from a wax-impregnated leather. The design is essentially that of a very small 18th century portmanteau. Included here are some of the basic tools-of-the-trade for scale and perspective. I think leather work is appealing to me, in part, due to the honest simplicity and lack of power tools. Most projects can be accomplished with a sharp knife, straight-edge, awl and some stitching needles.

This certainly is not anything fancy but it will do the trick.

This certainly is not anything fancy but it will do the trick.

Leather Laptop Case

I needed a new laptop case and had some nice shoulder leather left over from other projects. It’s a fairly minimalist design but serves to protect the little Mac. A small brass button closure is the only hardware.

I needed a new laptop case and had some nice shoulder leather left over from other projects. It’s a fairly minimalist design but serves to protect the little Mac. A small brass button closure is the only hardware.

After giving this some thought, I realize that a leather case like this should last at least 50 years, possibly more. The lifespan of a computer is about five years so this might end it’s service life as a document holder of some sort. It will make a great music case or something to hold a sketchbook somewhere down the road.

After giving this some thought, I realize that a leather case like this should last at least 50 years, possibly more. The lifespan of a computer is about five years so this might end it’s service life as a document holder of some sort. It will make a great music case or something to hold a sketchbook somewhere down the road.

Henry Miller, a fine young man

Definitely watch this if you believe in a real handcrafted lifestyle. He has obviously been given the right encouragement and access to knowledge. Many parents would scoff at these things or actively discourage some of these activities. I’m glad to know there are other parents out there with an open mind and encouraging this thirst for knowledge. It’s a fire waiting to be fanned.

Nicolás Lizares Huarachero in Tapalpa, Jalisco

What a beautifully shot movie about 80 year old Huarachero Nicolás Lizares.

For more detailed photographs check out a previous post titled Nicolás Lizares – Maker of Fine Huaraches from Tapalpa, Jalisco

Banjo redo

Last winter I had an important epiphany about myself as a musician. I am under nor delusion that I will ever be more than a closet or campfire player. For me, for now, that’s going to have to be good enough. Although I love the fiddle more than any other instrument, I went back to my roots and picked up a Deering Good Time five string banjo a couple years back to see if I couldn’t revive my banjo playing. I hadn’t really played much in over a decade but discovered that not only did the brain still remember some old tunes, but my big, beat-up fingers were actually still suited to it. Ham-hands I’ve heard them called!

After playing the “Good Time” for a couple years, I felt I outgrew it as a player. Don’t get me wrong, it’s a great instrument for the price (ca. $650), American-made, and travels well but I just wanted a little more substance and a thumpier traditional sound. Not being able to afford anything fancy, and my playing not really being up to any professional par, spending a load of money I don’t have was out of the question. It became apparent to me that it was time to make something better myself. This isn’t quite as outlandish as it may seem as in my woodworking days in my early twenties, I made a couple banjos, a handful of mountain dulcimers, and some mandolin parts that were fair to partly decent instruments. Anybody who knows me knows I hoard parts and hardware so fortunately I had a set of tuners, some fret wire, a tension ring, and a bracket set for a banjo (obviously the universe conspired for this to happen). For the rest, a quick trip through the Stewart-MacDonald catalog located the missing elements (e.g., a White Lady Vega-style tone ring, brass arm rest, bridge, and tailpiece, as well as a maple neck blank and rosewood fingerboard, and a calf-skin for the head).

Unfortunately, time and energy were against me when I made the initial build last summer. I was traveling and teaching for the university while working on this so I didn’t document the process. So, I essentially built this one twice. Once, to have something to play while traveling over the summer, then a rebuild in the fall to tweak the set-up and put a better finish on it (tung oil). The photos don’t really do it justice here but hopefully, it gets the idea across. Making an instrument is a doable thing.

Unfortunately, time and energy were against me when I made the initial build last summer. I was traveling and teaching for the university while working on this so I didn’t document the process. So, I essentially built this one twice. Once, to have something to play while traveling over the summer, then a rebuild in the fall to tweak the set-up and put a better finish on it (tung oil). The photos don’t really do it justice here but hopefully, it gets the idea across. Making an instrument is a doable thing.

I won’t even attempt to describe the process and there are many better instrument makers who have done this before me (see the Foxfire books, Irving Sloane, Earl Scruggs and plenty of others).

To make a banjo, you essentially need a few, more-or-less mechanical parts, then find a way to attach them together in a fairly precise and meaningful way; that is to say a neck, complete with a fretted fingerboard and tuners, and a drum-headed hoop of some type. Having some experience with steam bending, this part was not as intimidating as it might seem the first time around. My choice for the body was a hickory core with walnut laminates for the outside.

These pictures already show the six months of use and she already needs a good cleaning. As can be seen though, there’s little ornamentation on the instrument; no inlay or bindings, just an octave marker on the side of the fingerboard. I did steal the peghead design from Earl Scruggs’ book where he stole and printed the Mastertone design himself. It was just too classic.

I had intended to veneer over the back but after completion, I liked the raw look that shows the construction. Maybe I’ll change my mind about this later but for now, this is it. The calfskin head can be a finicky when traveling as it is affected by humidity. Some players remedy this with a thin layer of spray-on silicone. I may try this in the future just to see how it works.

I rarely see a reason to hide a beautiful wood grain.

The components that make up the pot of the banjo are illustrated above. From right to left: brass tension hoop, edge of the rawhide over wire, nickel-plated tone ring, tension brackets, and wood hoop. the armrest is just visible in the lower right.

It’s remarkable how fast the weight adds up. 24 brackets, brass screws, tone ring, tension ring, tuners, and armrest make for some significant weight. I think it’s a good idea for any artisan to sign their work, even if it’s never intended to sell. This separates the hand-crafted from the mass-produced and show the care and the soul that goes into a hand-made work.

Now, time to practice.

Makers to the Rescue

Makers, Dreamers, Builders, and Inventors, Unite:

reflections on saving our world

“Perpetual devotion to what a man calls his business, is only to be sustained by perpetual neglect of many other things. And it is by no means certain that a man’s business is the most important thing that he has to do” Robert Louis Stevenson.

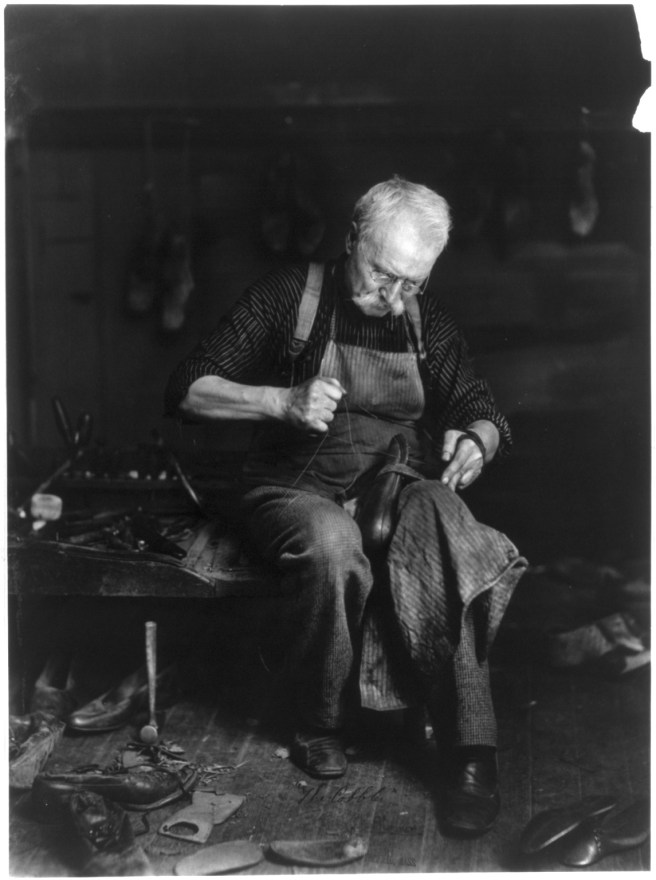

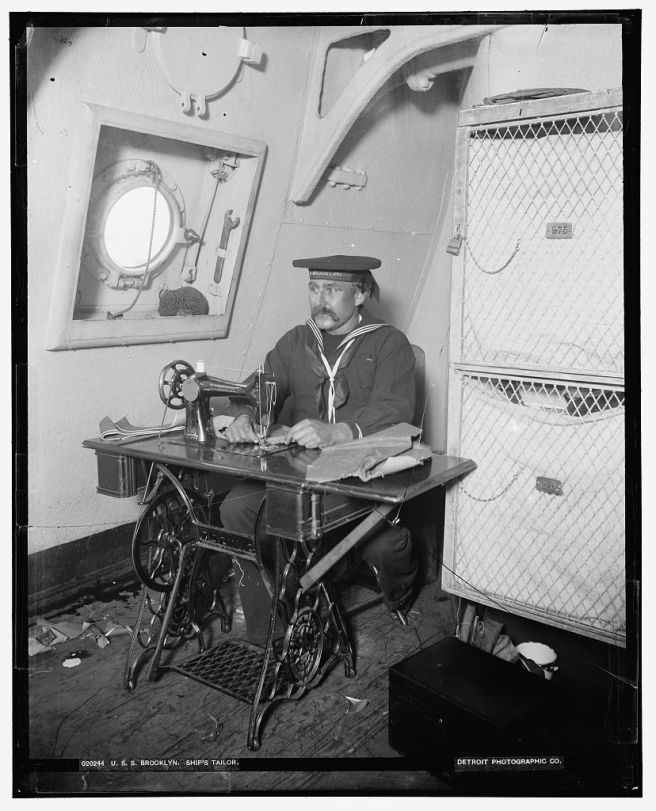

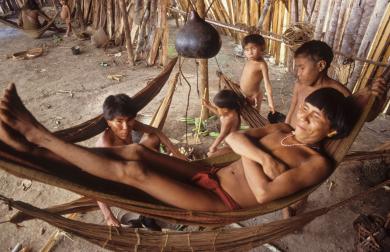

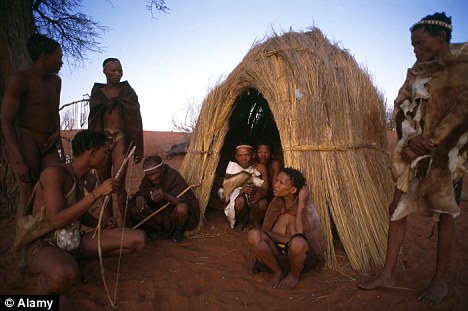

Humans are, by nature, makers of things. That’s how we deal with the world… or did, until the Industrial Revolution tore us away from our connection with the earth. Somebody is still making all the stuff, of course, its just outsourced and corporatized, repackaged, and branded. Strangely, the stuff that should last, like clothes, housing, or tools are generally poorly made and often unfixable while the junk that should be disposable is made from plastics that will endure for a geologic age or poison our descendents. But maybe, with a little effort, it doesn’t have to be this way.

Today, instead of procuring our needs directly or through someone we know, we trudge off into an abstract man-made environment to be treated as children and told to perform an obtuse task or two or twenty. And in exchange for giving up our time, we get slips of paper (or more likely, digits only readable to a computer on a plastic card) that confirm that we have performed our work and are now in a position to gather food, shelter, clothing, heat, etc. from a middle-man where profits are almost never seen by the makers.

Creating things like fire, rope, or cutting tools, not to mention shoes or housing will baffle most modern people. Weaving a blanket, sewing a shirt, or butchering an animal are simply out of the question for most of us in the western world. Many of these activities will get you strange looks at best or a call to the authorities at worst. This mindset means that most of us can’t feed or cloth ourselves any longer even if we really want to.

Makers are the hope. We’re out there. Doing things and making stuff. Fending for ourselves in an hostile but lethargic world of expected and nearly enforced consumerism. Once you realize the machine doesn’t work, you can realize it doesn’t really exist.

Makers are the hope. We’re out there. Doing things and making stuff. Fending for ourselves in an hostile but lethargic world of expected and nearly enforced consumerism. Once you realize the machine doesn’t work, you can realize it doesn’t really exist.

Most of my adult life, I’ve noticed an interesting paradox. Typical wage-slaves who proudly give 50 hours per week to a faceless and unappreciative mechanism are convinced that the dreamers and the creators are just a bunch idlers and flâneurs when it’s, in fact the lifestyle that they really envy. If it isn’t recognized as drudgery, somehow it’s not real work. But how much do we really need to be happy?

As a side note, many modern philosophers trace this thinking directly to the Protestant Reformation when, as they claim, much of the fun was beaten out of life and holidays were things to be frowned upon. But here I digress.

The internet actually gives me hope, especially seeing the wonderful documentaries of real craftsmen and makers around the world that are emerging from obscurity. Maybe to many, Makers are just a novelty. Something to be ogled at. But knowing there are others out there looking for a deeper purpose and a better existence makes me feel a little better about humanity.

Let’s be realistic; most modern folks wouldn’t opt to live as hunter gatherers as their ancestors did, but maybe we can reach a better balance with our lives than to adopt the imposed role as absolute consumers. And hopefully conscience people can do some good things along the way. Maybe by thinking outside the consumer mindset and choosing to build our homes, make our own socks and shirts, ride a bike, and hunt our meat we can make a difference by both our action and our inaction.

In the words of Samuel Johnson, “To do nothing is within everyone’s power.”

Remember: “An idle mind is a questioning, skeptical mind. Hence it is a mind not too bound up with ephemeral things, as the minds of workers are. The idler, then, is somebody who separates himself from his occupation: there are many people scarcely conscious of living except in the exercise of some conventional occupation”

Robert Louis Stevenson, idler extraordinaire.

Why not go make something? Your great grandparents did.

Why not go make something? Your great grandparents did.

P.S. Pardon the Friday late night ramblings. My disdain for the modern world is heightened at the end of a ridiculous week at work.

Bucksaw Again

For this project I moved my little operation into the living room of the house. Creating sawdust and wood chips for the dogs to track around in their boredom is a real bonus. But, on to the show…

Making a Bucksaw for carpentry, bushcraft, or just because they’re cool.

The little bucksaw I built last winter had never been “finished” even though I’ve been using it for a while now. Having a few hours to spare I pulled out the knives, rasps, and scraper and decided to finish this once and for all before getting down to the next project.

The little bucksaw I built last winter had never been “finished” even though I’ve been using it for a while now. Having a few hours to spare I pulled out the knives, rasps, and scraper and decided to finish this once and for all before getting down to the next project.

I hope to put this together soon as a sort of “Instructable” for making frame saws, buck saws, and turning saws but for now, this will have to do. Although common enough for the last couple millennia, frame saws have lost their place in the tool kits of carpenters and craftsmen, having been replaced by sabre saws, band saws, and the like. There is a lot of beauty in the old design and a serviceable saw can be built in a short time with very few tools. In fact, the one pictured here cost about $4 for the partial band saw blade, maybe a dollar for the screws and a few bucks for the long-toothed firewood blade. The lumber was created from a less-than-perfect bow stave; a well-seasoned shagbark hickory bodged down to about 7/8″ thick. The genius of this design is that it allows for an extremely thin blade to be stretched very tight for ease of work and a very clean cut.

A new, high quality band saw blade can be purchased for under $14 from a decent hardware store. The above is a Delta brand 1/2″ blade with 6 teeth-per-inch (TPI) and is only 2/100ths of an inch thick. That makes for very little waste which can be especially valuable when working harder to acquire materials like antler or bone.

Band saw blades are made in a continuous loop and are great for what they do but the first thing we need is to break the loop. The metal is extremely hard, and fairly brittle which works to our advantage. The edge of a sharp bastard file, like that pictured above can be used to score cross the blade. You don’t need to cut all the way through, but just make a solid scratch across the surface. Then the blade can be snapped by hand, making sure to not put any unnecessary bends in the blade. Drilling the holes in the ends is the tough part. As I said, the metal is very hard so, either you can use a punch to make a starter spot and drill through as is (but this will severely dull most drill bits), or the ends can be gently annealed in a forge or with a torch and drilled soft.

Band saw blades are made in a continuous loop and are great for what they do but the first thing we need is to break the loop. The metal is extremely hard, and fairly brittle which works to our advantage. The edge of a sharp bastard file, like that pictured above can be used to score cross the blade. You don’t need to cut all the way through, but just make a solid scratch across the surface. Then the blade can be snapped by hand, making sure to not put any unnecessary bends in the blade. Drilling the holes in the ends is the tough part. As I said, the metal is very hard so, either you can use a punch to make a starter spot and drill through as is (but this will severely dull most drill bits), or the ends can be gently annealed in a forge or with a torch and drilled soft.

Here are all the components of the new buck saw with the new linseed oiled surface glaring in the sun. The tensioner can be made from any strong cord (in this case 550 paracord), but any strong line can be built up or bailing wire will work (but is a little low-class and ugly and difficult to remove quickly). The spreader bar (the horizontal piece) is morticed into the legs but is not fastened by anything other than the tension on the whole system. Thus, the whole saw can be taken down in a few seconds and stuck into a toolbox or backpack for easy travel.

Here are all the components of the new buck saw with the new linseed oiled surface glaring in the sun. The tensioner can be made from any strong cord (in this case 550 paracord), but any strong line can be built up or bailing wire will work (but is a little low-class and ugly and difficult to remove quickly). The spreader bar (the horizontal piece) is morticed into the legs but is not fastened by anything other than the tension on the whole system. Thus, the whole saw can be taken down in a few seconds and stuck into a toolbox or backpack for easy travel.

Above is the assembled saw under tension and ready to cut. A good question was already asked as to “why the spreader is curved in this case?” Because this was made from real wood, split with and axe, following the grain. I could have worked to straighten it for looks but I like the fair curve it created and, as it has no bearing on the function, left it as is.

Above is the assembled saw under tension and ready to cut. A good question was already asked as to “why the spreader is curved in this case?” Because this was made from real wood, split with and axe, following the grain. I could have worked to straighten it for looks but I like the fair curve it created and, as it has no bearing on the function, left it as is.

Hope this helps anyone wanting to make a saw like this. Maybe I can offer this as a short, one day class at Rabbitstick or Winter Count soon.

Up soon: a turning saw.

Bike Storage

Saw this posted on Facebook:

The ultimate picnic bike. I like the fact that it is a bar on wheels but you could also pack i full of less fun stuff like food, tools, spare parts, or other flat goodies. There could be some cross-wind issues but the location is low and centered in the frame. Good use of space.

The ultimate picnic bike. I like the fact that it is a bar on wheels but you could also pack i full of less fun stuff like food, tools, spare parts, or other flat goodies. There could be some cross-wind issues but the location is low and centered in the frame. Good use of space.

Robin Wood, Traditional Craftsman

Here’s another excellent video of Robin Wood, wood turner and traditional craftsman. Visit his website to learn more about this remarkable man and his admirable career choice. As he explains, his job is easy to describe while so many careers are just about impossible to explain what one does and we create fancy titles to describe what we do all day.

His website is: http://greenwood-carving.blogspot.com/