Last winter I had an important epiphany about myself as a musician. I am under nor delusion that I will ever be more than a closet or campfire player. For me, for now, that’s going to have to be good enough. Although I love the fiddle more than any other instrument, I went back to my roots and picked up a Deering Good Time five string banjo a couple years back to see if I couldn’t revive my banjo playing. I hadn’t really played much in over a decade but discovered that not only did the brain still remember some old tunes, but my big, beat-up fingers were actually still suited to it. Ham-hands I’ve heard them called!

After playing the “Good Time” for a couple years, I felt I outgrew it as a player. Don’t get me wrong, it’s a great instrument for the price (ca. $650), American-made, and travels well but I just wanted a little more substance and a thumpier traditional sound. Not being able to afford anything fancy, and my playing not really being up to any professional par, spending a load of money I don’t have was out of the question. It became apparent to me that it was time to make something better myself. This isn’t quite as outlandish as it may seem as in my woodworking days in my early twenties, I made a couple banjos, a handful of mountain dulcimers, and some mandolin parts that were fair to partly decent instruments. Anybody who knows me knows I hoard parts and hardware so fortunately I had a set of tuners, some fret wire, a tension ring, and a bracket set for a banjo (obviously the universe conspired for this to happen). For the rest, a quick trip through the Stewart-MacDonald catalog located the missing elements (e.g., a White Lady Vega-style tone ring, brass arm rest, bridge, and tailpiece, as well as a maple neck blank and rosewood fingerboard, and a calf-skin for the head).

Unfortunately, time and energy were against me when I made the initial build last summer. I was traveling and teaching for the university while working on this so I didn’t document the process. So, I essentially built this one twice. Once, to have something to play while traveling over the summer, then a rebuild in the fall to tweak the set-up and put a better finish on it (tung oil). The photos don’t really do it justice here but hopefully, it gets the idea across. Making an instrument is a doable thing.

Unfortunately, time and energy were against me when I made the initial build last summer. I was traveling and teaching for the university while working on this so I didn’t document the process. So, I essentially built this one twice. Once, to have something to play while traveling over the summer, then a rebuild in the fall to tweak the set-up and put a better finish on it (tung oil). The photos don’t really do it justice here but hopefully, it gets the idea across. Making an instrument is a doable thing.

I won’t even attempt to describe the process and there are many better instrument makers who have done this before me (see the Foxfire books, Irving Sloane, Earl Scruggs and plenty of others).

To make a banjo, you essentially need a few, more-or-less mechanical parts, then find a way to attach them together in a fairly precise and meaningful way; that is to say a neck, complete with a fretted fingerboard and tuners, and a drum-headed hoop of some type. Having some experience with steam bending, this part was not as intimidating as it might seem the first time around. My choice for the body was a hickory core with walnut laminates for the outside.

These pictures already show the six months of use and she already needs a good cleaning. As can be seen though, there’s little ornamentation on the instrument; no inlay or bindings, just an octave marker on the side of the fingerboard. I did steal the peghead design from Earl Scruggs’ book where he stole and printed the Mastertone design himself. It was just too classic.

I had intended to veneer over the back but after completion, I liked the raw look that shows the construction. Maybe I’ll change my mind about this later but for now, this is it. The calfskin head can be a finicky when traveling as it is affected by humidity. Some players remedy this with a thin layer of spray-on silicone. I may try this in the future just to see how it works.

I rarely see a reason to hide a beautiful wood grain.

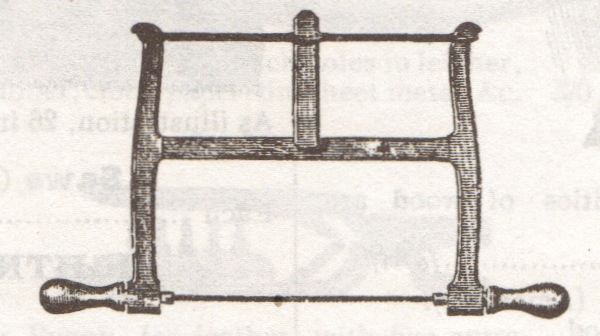

The components that make up the pot of the banjo are illustrated above. From right to left: brass tension hoop, edge of the rawhide over wire, nickel-plated tone ring, tension brackets, and wood hoop. the armrest is just visible in the lower right.

It’s remarkable how fast the weight adds up. 24 brackets, brass screws, tone ring, tension ring, tuners, and armrest make for some significant weight. I think it’s a good idea for any artisan to sign their work, even if it’s never intended to sell. This separates the hand-crafted from the mass-produced and show the care and the soul that goes into a hand-made work.

Now, time to practice.