Visit the Huarache Blog.

Category: shoes

Project: Mayhem Shoes

“The first rule of Project Mayhem is that you do not ask questions…”

this may be my new teaching mantra

I am considering calling my custom footwear “Mayhem Shoes” (at least until Chuck Palahniuk’s space monkey lawyers make me stop).

I teach a couple classes about low-tech shoemaking a few times per year in the primitive survival skills community. The designs I focus on are styles that can be made by one person in one day; a popular theme in early historic examples. Some require a lot of cutting, some require sewing. There is an off-grid, dystopian attitude about making your own shoes. In fact, I think I will register the name Distopian Leather Works as my new business. I’m considering a small business venture to go into custom production of the shoes I teach people to make as well as expanding the custom leather work I currently produce.

The kinds of people that take these classes are from all walks of life, not just survivalists, historical nerds, or experimental archaeologists, but folks who want to make things for themselves for whatever reason. I’m finding that there are others who might just want the handmade product without the labor of making them.

The kinds of people that take these classes are from all walks of life, not just survivalists, historical nerds, or experimental archaeologists, but folks who want to make things for themselves for whatever reason. I’m finding that there are others who might just want the handmade product without the labor of making them.  In a day, an attentive student can produce a wearable (and good looking) pair of serviceable shoes like the carbatana (ghillies) above.

In a day, an attentive student can produce a wearable (and good looking) pair of serviceable shoes like the carbatana (ghillies) above.

For those looking for a more modern look a fine pair of sandals can be made with just a few hours, cutting and sewing. These are easily re-solable and should last the better part of a lifetime. Look familiar? Chaco and Teva didn’t exactly re-invent the wheel; just updated the materials and outsourced the work overseas.

For those looking for a more modern look a fine pair of sandals can be made with just a few hours, cutting and sewing. These are easily re-solable and should last the better part of a lifetime. Look familiar? Chaco and Teva didn’t exactly re-invent the wheel; just updated the materials and outsourced the work overseas.  Even in the wilds of Canada, tradtional ghillies can be a useful part of the wardrobe. Mike made these two years ago and they still protect his sturdy peasant feet.

Even in the wilds of Canada, tradtional ghillies can be a useful part of the wardrobe. Mike made these two years ago and they still protect his sturdy peasant feet.

There is something very satisfying about taking a piece of nondescript, vegetable tanned leather and creating a lasting and useful object with your own hands.

There is something very satisfying about taking a piece of nondescript, vegetable tanned leather and creating a lasting and useful object with your own hands.

The beauty is truly in the details. Serious students often bevel and burnish edges to give their shoes a “finished” look, suitable for public wear.

The beauty is truly in the details. Serious students often bevel and burnish edges to give their shoes a “finished” look, suitable for public wear.

Above, a student trial fits the uppers before attaching the outsole. In my classes, the outermost sole on any of these shoes may be a durable Vibram material, a softer but grippy Soleflex, or natural leather. The latter option is popular with those who are interested in treading lightly on the earth or those who are concerned with earthing or grounding.

Learning as community. It is always a very social event to teach these courses. No matter the variety of backgrounds, we are sharing an ancient craft in common.

Learning as community. It is always a very social event to teach these courses. No matter the variety of backgrounds, we are sharing an ancient craft in common.

As in all leatherwork, neatness counts. A good hand with a knife is a great asset for shoemaking.

Test fitting the straps for buckle placement and strap length.

Test fitting the straps for buckle placement and strap length.

This style sandal may be tied or buckled but I have found that a 3/4″ center bar buckle is about the easiest to work with and adjust.

This style sandal may be tied or buckled but I have found that a 3/4″ center bar buckle is about the easiest to work with and adjust.

Bowing to modern convenience. For the classes, we use contact cement to adhere the insole, mid-sole, and outsole. This insures a good connection and will hold up even if the stitching doesn’t last forever.

Bowing to modern convenience. For the classes, we use contact cement to adhere the insole, mid-sole, and outsole. This insures a good connection and will hold up even if the stitching doesn’t last forever.

The author demonstrates the wrong way to rough out a pattern. Cutting out oversize pieces for the sake of time-savings.

The author demonstrates the wrong way to rough out a pattern. Cutting out oversize pieces for the sake of time-savings.

Tough rubber soles will make these sandals last years and are easily replaced.

Tough rubber soles will make these sandals last years and are easily replaced.

Trial fitting a ghillie after soaking in water. They feel ridiculously thick and stiff for the first hour or two but tend to suddenly relax an become a part of the foot after a soak in the neatsfoot oil.

Trial fitting a ghillie after soaking in water. They feel ridiculously thick and stiff for the first hour or two but tend to suddenly relax an become a part of the foot after a soak in the neatsfoot oil.

Ready for staling the game or dancing at a cèilidh

Ready for staling the game or dancing at a cèilidh

Sometimes it helps to take a hammer to the leather when it is stiff and wet.

Sometimes it helps to take a hammer to the leather when it is stiff and wet.

It is important to leave the channels free of glue so that the straps may be adjusted in future. You never know when you might need to wear some black socks with those sandals.

It is important to leave the channels free of glue so that the straps may be adjusted in future. You never know when you might need to wear some black socks with those sandals.

Helping a student skive out some particularly stiff areas.

Helping a student skive out some particularly stiff areas.

Mom tries on her new shoes before going home to make some for the whole family.

Mom tries on her new shoes before going home to make some for the whole family.  Even an old shoemaker is interested in this ancient design.

Even an old shoemaker is interested in this ancient design.

Happy and diligent students show off their newest creations.

Happy and diligent students show off their newest creations.

Above are few photos from previous classes. Thanks to all who come and make!

Irish Brogues and Other Simple Shoes

It’s time for new shoes. After a soon-to-be-finished commission for a leather satchel, I intend to dive into a brogue-making project in the style of 19th century Ireland. This basic design certainly dates back much further than this as shown by archaeological finds in bogs throughout Europe. Don’t confuse these brogues with the more modern usage such as:

This is a brogue in the Scottish/Northern English semi-formal fashion with decorative holes reminiscent of the drains left in old field shoes. Nor is this to confused with the type of shoe that some modern-primitives call “ghillie-brogues” or more properly, just “ghillie”:

This is a brogue in the Scottish/Northern English semi-formal fashion with decorative holes reminiscent of the drains left in old field shoes. Nor is this to confused with the type of shoe that some modern-primitives call “ghillie-brogues” or more properly, just “ghillie”:

These earned their proper name from Scottish Ghillies; a term used to denote game wardens, hunting and fishing guides, and sometimes, even poachers. A simple shoe style that probably goes back several millenia in Europe.

What I decided to shoot for was a shoe that is relatively simple to produce, is closed for winter use, and can be regularly worn in public without arousing too much comment.

To me, something like the “bird shoe” above is very cool but not really acceptable in an unforgiving office environment. I would gladly hunt elk in these but for some reason, modern work culture has a fairly standardized and limited uniform. This style tends to be cut from a single piece and sewn around three-quarters of the sole. This one is punch decorated, probably to show off the stockings inside, a sign of wealth. This is a form of “turn-shoe” or soft-sole sewn inside-out then “turned”. A sturdy high top 12th century Dutch example with a center-seamed upper is seen below. In my opinion, these would make a fine winter shoe.

I can’t help but see the similarity between these and North American center-seam moccasins.

The style above is a well-documented Irish “Type 1” dating anywhere from the 1st centuries A.D. through the Middle Ages. A little more complex in construction, especially to get a perfect fit, it has been argued that these may be the result of craft specialization in the early Christian period of Northern Europe. I plan to make a pair of these and contemplate them as a possible design for teaching simple shoemaking. There is some real sewing involved, but not enough to intimidate most beginners.

The style above is a well-documented Irish “Type 1” dating anywhere from the 1st centuries A.D. through the Middle Ages. A little more complex in construction, especially to get a perfect fit, it has been argued that these may be the result of craft specialization in the early Christian period of Northern Europe. I plan to make a pair of these and contemplate them as a possible design for teaching simple shoemaking. There is some real sewing involved, but not enough to intimidate most beginners.

For those who know American moccasin styles the pattern above seems very familiar as a one piece, side-seam shoe.

So, this brings us to the “Irish Brogue” or Type 5 shoe. These are known well up into the nineteenth century and I wouldn’t be surprised to find them in even more modern contexts, especially amongst the poorer populations. There are similar shoes depicted in Colonial America, probably made in the home for lack of money or access to a cordwainer.

The above brogues appear to be a “built” shoe, having separate soles, multi-pieced upper, and a heel lift; the only difference between these and others from the period is the lack of ties or buckles. Although difficult to tell from the image, they are likely constructed similar to those below:

Hopefully, updates will soon follow to track the creation of a new pair of shoes.

Another Huarache Design

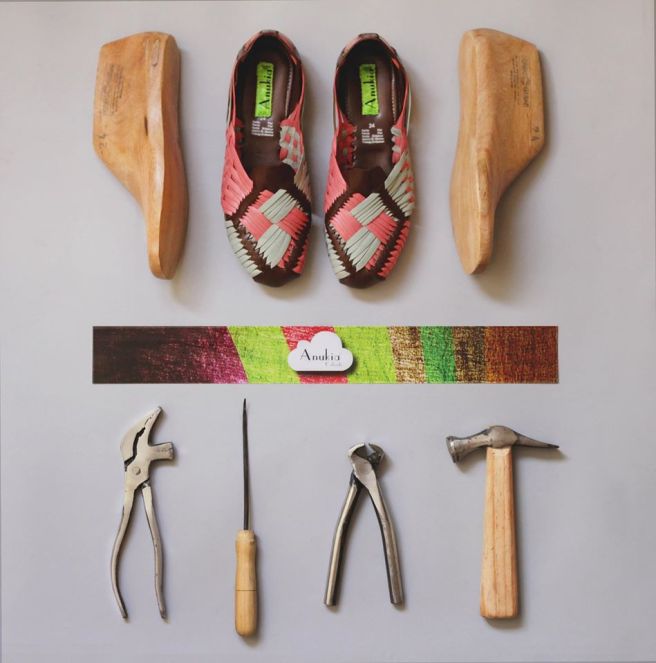

I like the closed, round toes on this one. From http://huaracheblog.wordpress.com/.

Le Cordonnier

The Shoemaker

A real treat from the Sifting the Past blog. It is worth checking out if you are interested in researching the past through images of the period just prior to mass industrialization. The Townsend’s have a couple excellent websites including an interesting 18th century cooking blog with videos. There is so much in this painting that describes the time and the craft of the cordwainer. There is a palm awl and lasting pinchers in the lower right, the ever critical strap for holding the shoe while sewing, the sewer’s palm for pulling tight the lock stitch, as well as the hammer, mallet, and knife of the trade. He is holding the sole awl in his left hand. The basket on the work bench contains a great bone tool made from a metapodial bone as so often found prior to the 20th century when craftsmen made their own tools. I want my shop to look this great sometime soon.

Huaracheria Aquino in Yalalag, Oaxaca (reblogged)

This is a great series of photos of a surviving craft still producing their own leather. This maintains an economy (for them) that could have very little cash outflow, replacing the cost of raw materials with labor. I hope these industries survive.

- A great photo of a huarachero from the series.

Nestled into the Sierra Norte mountains of Oaxaca is the small town of Yalalag.

Yalalag is very precious town, not only for it’s strong Pre-Hispanic traditions, but also because like only a handful of other small towns in Mexico, most of the Yalalag population is still dedicated to the traditional craft of Huarache making.

Huaracheria Aquino is the largest ‘Taller’ workshop in Yalalag and they are well known for their high quality Zapotec Huaraches.

What also sets this family run business apart from most other Huarache makers in Mexico is that their crafting process begins at their in-house tannery, where they vegetable tan all their leathers to their precise specifications.

Huaracheria Aquino is famous for their traditional women’s Zapotec Yalalag sandals (the only existing traditional women’s leather sandal/huarache style in Mexico).

Photo of young Zapotec Woman in Mitla, by Guy Stresser-Péan, 1957

Their ‘Tejido’ Huarache also stands out for the…

View original post 153 more words

The Shoemaker’s Shop

Prang’s Aids For Object Teaching written by Norman Allison Calkins in 1877. From the Shoemaker’s Shop, Colonial Williamsburg.

Huarache Blog

If you are interested in Huaraches, this blog is the end-all of huarache information.

Señor Alfaro is 70 years old and the last Huarachero in Sayula, Jalisco. Although his woven Huaraches have won him awards in regional craft competitions, today like may Huaracheros his business has become very difficult. Although Señor Alfaro has done very well to stay in a trade where many have quit, he melancholically tells me that Huarache making is a craft headed for extinction and that he has advised all his family not to get into it.

Sadly most towns in Mexico have at most one Huarachero left, whereas 30 years ago each town used to have many. Señor Alfaro told me that at one time 90% of Sayula locals wore Huaraches and 10% wore shoes, today that ratio is inverted and only 10% wear Huaraches.

But besides the reduced consumer base, there are 2 major difficulties facing skilled Huaracheros today, the rising costs of vegetable tanned leather and rubber tyres, and that…

View original post 163 more words

Huaraches!

There are Huaraches north of old Mexico.

As a craftsman of sorts, I understand that making a “one-off” of something does not imply expertise and replication builds a real understanding of the object being produced. However, this is certainly not my first leather working or shoemaking project but a major improvement on a theme. The lasts I purchased earlier in the year on Ebay have finally been used to actually make a shoe so I documented the process as it came along last week; mistakes and changes included in the process. While searching for huarache construction, I have only been able to find the simplest tire sandal designs and many links to “barefoot” running sandals. I recently found the Huarache Blog and scoured it for inspiration and design secrets from real huaracheros in old Mexico.

The lasts shown here seem to fit me well but are an Oxford dress shoe style, I think, meaning they run a little long in the toe. New lasts are pricey (ca. 50 euros/70 US), but I think it will pay in the long run to invest in a better design for myself and those people I might make shoes for.

I didn’t show the strap cutting process as there is little to be learned about that. My fancy new Osbourne strap cutter can be seen in the upper right of this photo

Since this project was experimental, I used scrap leather, meaning I could only get about three foot (one meter) straps. In future, I’ll probably use 6 foot or longer pieces (2+ meters).

Pre-punched holes in the mid-sole and away we go. A little tallow on the straps helps cut the friction of the leather but ended up being not worth the trouble.

This is a signature of the style I chose. The vamp or tongue-like piece was later removed as I didn’t like the way it looked. I’ll experiment more with that later.

Unlike normal, I completely finished the first shoe and removed it from the last to check size and shape to determine any major changes that would need to be made.

The straps running under the mid-sole look like a problem here but are ultimately skived down, wetted, and hammered flat.

I used simple wire nails to attach the soles but sewing would work too.

Pulled from the last, they actually matched. I don’t know why I was surprised but that made me happy.

This method is fast and efficient, and I suspect rather tough. The nails are pressed through the leather and rubber into a thick leather scrap below. Otherwise, you would need to pry it up from the work board.

The nails are bent over (inward) to prepare to “clinch” them. There are no photos of this part of the process but this was done by setting the shoe back upright on a small anvil and hammering the nails down tight with a punch. The pre-bending causes the nail to curl inward and back up into the sole. Voila! The Huaraches below have about five miles of hiking on them now and they’re beginning to have some character.

Huaraches you say? Do tough guys wear such things? In an era of cheap, slave-made garments, its easy to forget how self-reliant our ancestors were for such things as raiment. I include this excellent photo of Capitan Alcantar I found on the Huarache Blog as a great historical image of a man of action wearing his huaraches and ready for war.